How I learned to listen while researching ways for utilities to support Indigenous food sovereignty

Many Indigenous communities around the world are committed to reducing emissions and halting climate change. However, these communities have frequently benefited less than others from clean energy funding and resources. Several years ago, a collection of Slipstream board members and staff recognized this inequity and began to discern how Slipstream might support the clean energy work of Native nations in the Midwest.

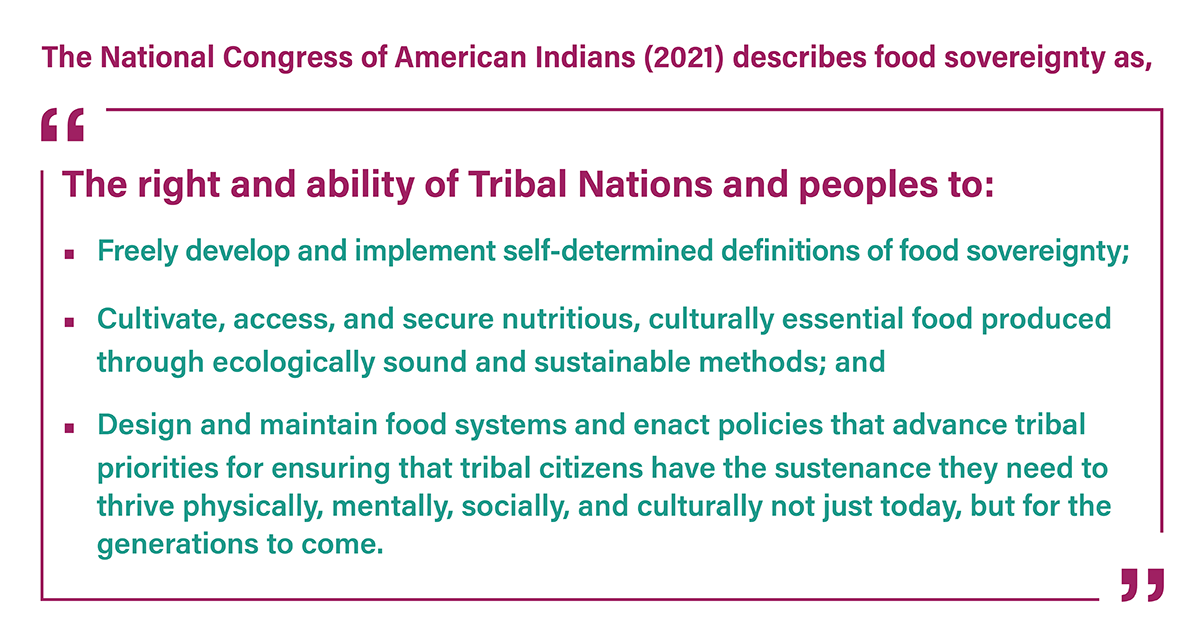

Native nations are sovereign, with corresponding rights to self-determination and distinct identities. Through colonization, many nations suffered forced migration away from their historic homelands. Loss of homelands, among other colonial interventions, disrupted traditional food systems, causing a shift from food sovereignty to food dependency.

Connecting the energy and emissions intensity of conventional food production and the importance of food sovereignty to many Native nations, Slipstream proposed a Minnesota CARD–funded research project to investigate how the state's Conservation Improvement Program (CIP) could support Indigenous food sovereignty work. I had the privilege of serving as the project manager for this research.

On a personal level, I am passionate about food. Meals in my childhood home and many-generational family recipes are bases for many of my warm foundational memories. Today, cooking and baking for my family are some of my favorite ways to share my affection with them.

I recognize the vast gulf between the value that I place on my culinary heritage and the value of traditional food ways in many Indigenous communities, but my own connection to food helped me understand these values and connect more deeply with the work.

I grew up in a home that valued equality. I saw my parents build lives and careers that centered around speaking up for people on the margins of society. So, starting this research project, I was excited about the opportunity to investigate how to support the flow of resources from pools of energy efficiency program funding to communities that may be underserved by clean energy programs.

During the research, the project team sought to speak with an array of Native nations and Indigenous producers who were involved in food sovereignty work. We wanted to learn about the agricultural, food processing, and transportation aspects of their work to find opportunities for connections with CIP funding requirements. We also asked the interviewees directly how CIP could support their work.

With good intentions in one hand and a list of interview questions in the other, a centuries-old legacy of dishonesty and mistrust confronted me during the first interview.

I am a middle-age, middle-income white man who lives near the top of the privilege pyramid. This identity likely contributed to the first interviewee responding to our questions with strong skepticism and a defensive posture. History spoke more loudly than my good intentions and this man sought to protect the traditional knowledge and ways that are embedded in Indigenous food sovereignty.

During that conversation and in future conversations, we recognized our limitations and focused on listening first. We encountered interesting, insightful, and creative people who were simultaneously innovating food systems and leveraging traditional knowledge. I was grateful for the opportunity to encounter amazing people and to do this work.

The research generated recommendations for immediate actions that Minnesota utilities can take to expand their CIP offerings to support Indigenous food sovereignty work, and its significant economic impacts, in their service territories. It also offered longer-term recommendations for how the state's regulatory framework could be adapted to more holistically value the benefits generated by CIP investments, thereby broadening the avenues through which utilities could apply CIP funding to support food sovereignty.

Along with recommendations to the State of Minnesota, the project reinforced my awareness of my privilege and of how that privilege can create barriers. It reminded me of the importance of listening first – especially if I think I know the answer. Lastly, it reminded me that communities that I want to serve know what they need and that I can support best when I listen first.