Healthy, affordable housing for all: It's the right thing to do

Environmental Justice is the right to a safe, healthy, productive, and sustainable environment, where "environment" is considered in its totality to include the ecological, physical, social, political, aesthetic, and economic environment. Environmental justice addresses the disproportionate environmental risks borne by low-income communities and communities of color resulting from poor housing stock, poor nutrition, lack of access to healthcare, unemployment, underemployment, and employment in the most hazardous jobs.

Community needs should drive housing solutions.

We have a shortage of 7 million affordable rental homes for people with household incomes at or below the poverty guideline. There is no "one size fits all" approach to this problem. You can't build a successful program without understanding the community's needs, and you can't describe the community until you know them. Instead, the Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ) and the Jemez Principles of Democratic Organizing guide us to build solutions with impacted communities.

The Principles of EJ have been widely used for grassroots organizing since their adoption at the 1992 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. These principles:

- Guide us to focus on unity and interdependence of people and the planet

- Demand mutual respect and justice for all people

- Affirm the right for all people to access resources, live in safe environments, and engage in political, economic, cultural, and environmental self-determination.

The Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing have been used since the 1996 Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice meeting to ensure all people a seat at the table. Much like the EJ principles, the Jemez Principles empower us to:

- Listen actively and involve all people in decision making

- Emphasize bottom-up organizing and relationship building,

- Commit to self-transformation as we learn from one another

- Invite all people to self-represent

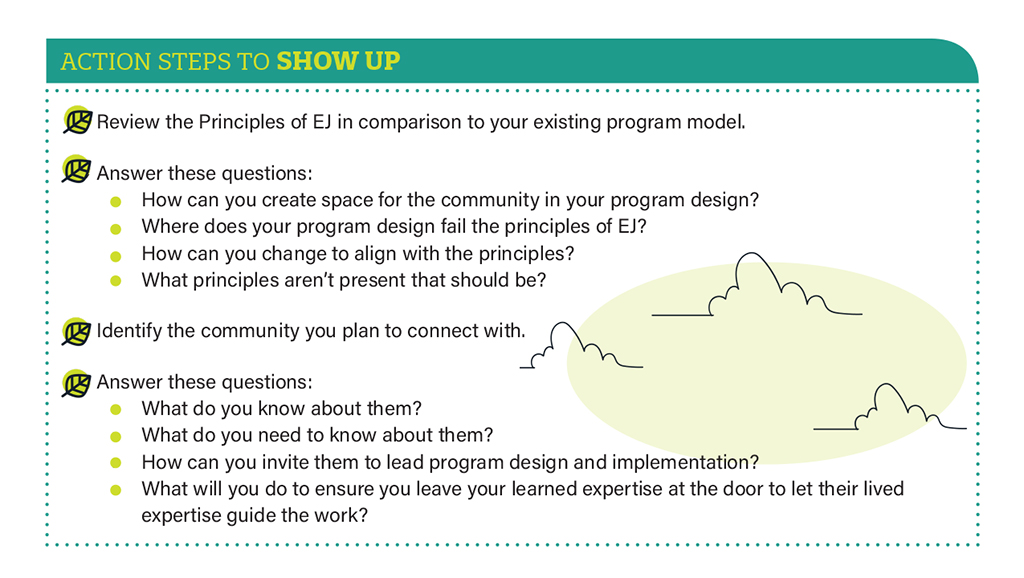

Guided by these principles, we offer a simple framework to design community-led solutions: "show up, listen actively, and practice care."

Show up with the 17 Environmental Justice Principles.

Principle of EJ 7: EJ demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making, including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation.

Jemez Principle 5—Build Just Relationships Among Ourselves: We need to treat each other with justice and respect, both on an individual and an organizational level, in this country and across borders. Defining and developing "just relationships" will be a process that won't happen overnight. It must include clarity about decision-making, sharing strategies, and resource distribution. There are clearly many skills necessary to succeed, and we need to determine the ways for those with different skills to coordinate and be accountable to one another.

Several years ago an energy industry connection introduced us to Growing Up Healthy in Minnesota, a local community group working to improve housing in manufactured home parks in their community. Residents had some of the highest winter water bills in the county because they constantly ran water to prevent pipes from freezing. Slipstream building science expert Adrian Scott showed up and trained residents on how to weatherize their homes.

We recently reconnected with Growing Up Healthy through the Justice40 Accelerator initiative. They shared their vision, along with its challenges, and asked: "how can you help us?" Growing Up Healthy staff are struggling to hire a manufactured home rehab coordinator and find trustworthy contractors to work on manufactured homes. They are also in talks with a variety of stakeholders (utilities, faith communities, city government, county government, nonprofits, etc.) about how to improve housing for families they support. Growing Up Healthy trusts us to show up again because we showed up to help them in 2019.

Utilities and governments often find communities like this one "hard to reach." Let's challenge that label. Existing solutions are based on what has worked in wealthy, white communities, not the frontline communities who need them most. Community members and groups bring creative solutions that make programs more effective.

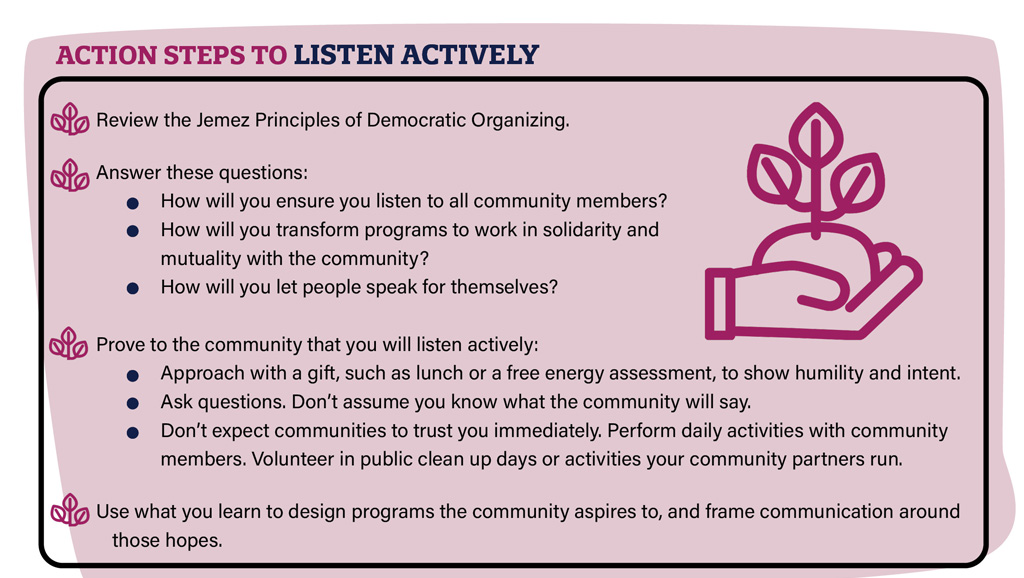

Listen actively with the Jemez Principles.

Principles of EJ 5: EJ affirms the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural and environmental self-determination of all peoples.

Jemez Principle 3—Let People Speak for Themselves: We must be sure that relevant voices of people directly affected are heard. Ways must be provided for spokespersons to represent and be responsible to the affected constituencies. It is important for organizations to clarify their roles, and who they represent, and to assure accountability within our structures.

Begin a community led project by showing up and listening. People have lived experiences, challenges, and joys that make them experts in their community. Based on what we learn from active listening, we can work with the community to determine if we have the tools, skills, and organizational will to adapt and support the community's priority initiatives. We must remember to not bring our own agenda to these discussions; patience and good listening skills go a long way.

The Community Development Corporation (CDC) of Pembroke and Hopkins Park in Illinois is leading an exciting weatherization and electrification demonstration project. One of the authors of this piece, Shannon Stendel, quickly learned the importance of listening to understand the project's goals and how Slipstream could best support it. Shannon also quickly learned the importance of following the community's lead, lending expertise when needed, and being flexible. Early in the project, the CDC put project partners in their place. The CDC viewed some project management suggestions from partners as trying to "micromanage" the project. The CDC knew how to effectively navigate the scope, resources, and timeline. We needed to listen, take a backseat, and recognize that we lack the expertise of the community, which we needed to implement the project.

Our home assessments identified a resident with an unvented propane heater who had taken batteries out of the carbon monoxide detectors because they beeped constantly. Through one-on-one conversations we explained how dangerous the situation was, and community members supported the resident based on what we explained.

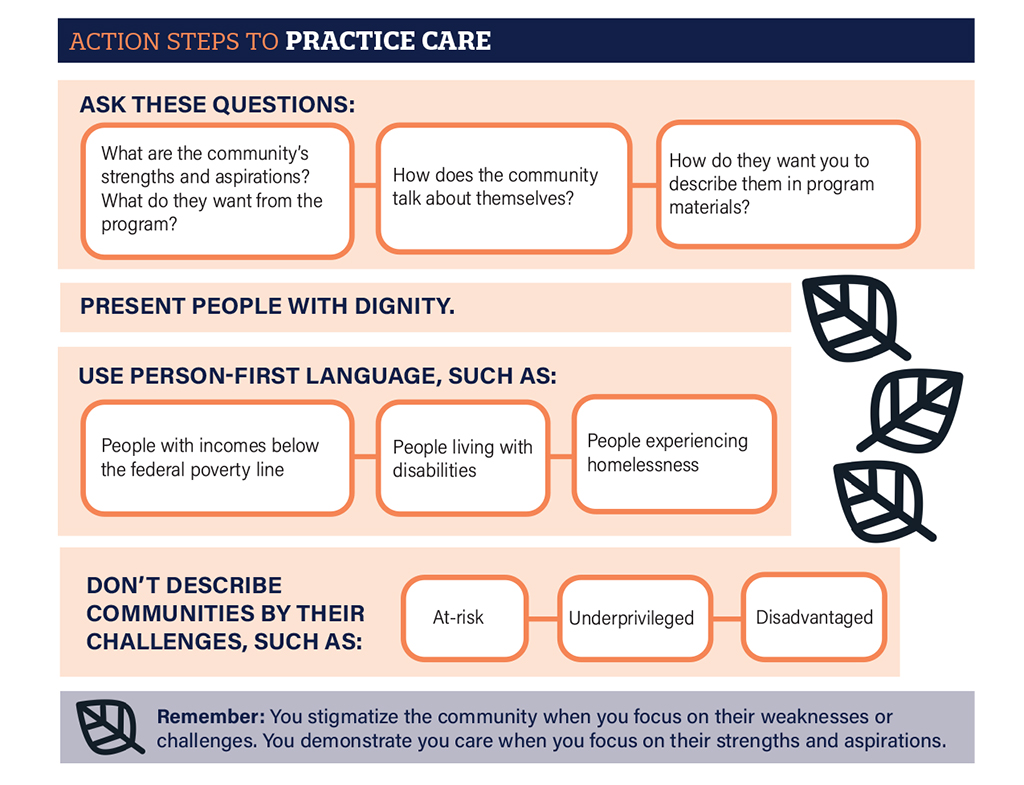

Practice care with asset framing.

Asset framing is the simple act of defining communities by their strengths and aspirations, not their weaknesses or challenges.

"One of the benefits of asset-framing is that when you state someone's aspirations, your brain instantly associates them with worthiness. It becomes much easier to see that the problem is not the person but situations and systems that block their worthy aspiration" - Trabian Shorters, CEO of BMe Community

Principle of EJ 16: EJ calls for the education of present and future generations which emphasizes social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives.

Jemez Principle 4—Work Together in Solidarity and Mutuality: Groups working on similar issues with compatible visions should consciously act in solidarity, mutuality and support each other's work. In the long run, a more significant step is to incorporate the goals and values of other groups with your own work, in order to build strong relationships. For instance, in the long run, it is more important that labor unions and community economic development projects include the issue of environmental sustainability in their own strategies, rather than just lending support to the environmental organizations. So communications, strategies and resource sharing is critical, to help us see our connections and build on these.

New affordable housing units only help a small sector. Many people already live in unsafe, unhealthy homes. They can't sell homes located in EJ communities — or they spend too much on energy to afford higher rent elsewhere. Only about 30% of homes are eligible for weatherization programs, meaning only 0.2% of households with low incomes are weatherized each year. Over 35% of homes require some level of home repair, and 6.6 million households with low incomes need home repairs.

Energy burdens for people with low incomes are often three times as much as the national median. This prevents people from financing home repairs and may make it difficult to participate in weatherization or utility programs that help lower energy burdens and improve home environments. For example, a low-income home may be deferred from receiving weatherization services due to excessive mold or moisture, a leaky roof, asbestos, or pests. Some programs address these "pre-weatherization" improvements and enable weatherization, but not universally.

Programs that provide critical home repairs are one of the biggest investments utilities and governments can make to care more about their communities. These programs change people's lives. These programs show that we, as a society, care for one another.

The 2021 Energy Conservation and Optimization (ECO) Act in Minnesota increased utility minimum spend requirements on programs for customers with low incomes and allowed new Conservation Improvement Program (CIP) spending on pre-weatherization measures.

Many communities use Community Development Block Grants to improve housing. For example, Slipstream recently partnered with Ramsey County, Minnesota on a critical home repair pilot program to deliver health and safety repairs to homeowners with low incomes.

Using asset framing to define a community differently is an act of care that will drive participation. People need to see themselves in the program design—represented the way they represent themselves—to participate.

Housing is a human right. Housing is the heart of environmental justice.

Across the country, affordable housing is increasingly inaccessible for people with low incomes, communities of color, and Indigenous communities. Systemic redlining, predatory lending practices, and racist zoning laws have denied people the opportunity to develop generational wealth. The result? People forced to live in highly polluted areas with low air quality, near toxic waste dumps, in housing that doesn't keep them safe.

We must prioritize safe, healthy housing for all to advance our climate and equity goals. The energy industry holds powerful tools:

- Technology to improve home health and safety

- Evidence of what works in various climate zones

- Financing programs to help lower energy burdens.

But our solutions are disproportionately available to white, wealthy households, even though the affordable housing crisis disproportionately impacts Black, Brown, Indigenous, and Immigrant communities. It is our responsibility to change that. We need to show up, listen actively, and practice care.

This article first appeared in the Q2 2022 issue of AESP's Energy Intel magazine.